Part Two: Life Beyond Residential School

Life Beyond Residential School

Booze, drugs, dysfunction, and the saving grace of ‘blameless shame’

By Eugene Arcand

When I got out of residential school at the age of 17, I didn’t give a s–t about anyone or anything. I was filled with hate.

It was nothing for me to get into all sorts of conflicts with the Settler community, including the police, for no reason. I was afraid of nothing. I had no fear. I had just done 11 years of hard time. You want to send me to jail again? Fine, I don’t give a s–t. That was the mentality and psychology I had. So, I went on a three-year binge of booze, drugs – anything I could ingest. I never put on a pair of skates during those first three years after residential school.

Then, at the age of 20, this incredible lady, my wife Lorna, came into my life. She was 18 and we were married in 1972. I don’t know how she put up with me, because for the next 15 to 20 years, I was still being a piss tank, a druggie, a scrapper. I lived two lives — the life of a dangerously dysfunctional person and the life of an athlete.

For a long time in our marriage, I never shared with Lorna any of the stories I’m sharing now with you. Once in a while I might say this or that happened but never to any great extent. I carried shame for having experienced deviant behaviour with adults, members of the clergy and other perverts who worked in those residential schools. It was not just me. I know today who abused who and when it happened. And I know how damaging it was to all those kids. And they know the same about me. We don’t talk about it in that graphic way. We just know we were traumatized children, who are damaged goods today. We are just trying to fix ourselves.

So, after this woman came into my life, I tried to straighten out, but I still didn’t really know how to love. I didn’t know how to grieve. I didn’t know how to hug. I was just this rank guy trying to survive in a world that was not normal to me. The only thing that felt normal to me was being on the ice, the soccer field, the rugby field, a volleyball court or basketball court.

Eugene Arcand and his wife Lorna, who work tirelessly on behalf of the North American Indigenous Games. (Photo Credit: Eagle Feather News)

Sports were my safe space. But then there was the reality of life. It didn’t take long for us to start having children. I had to adapt into that world of trying to work to support my family and still play sports. Most of my work was minimum wage. I washed dishes, piled cement blocks, I was a night watchman, but I was still leading a totally dysfunctional lifestyle.

Even well into my 30s, after 15 years of marriage, I still hadn’t really shared much of my trauma with Lorna. I gave her every reason to kick me out or leave me. But she stuck with me. I’m lucky she did. I thought I would end up in a maximum-security prison at some point or that I wouldn’t live to see today. That’s where I was headed, and I had no fear of it.

One day, a friend of mine asked me to go to the University of Saskatchewan to listen to a guest speaker. I reluctantly went. I had a hangover. I didn’t want to be there. I knew I didn’t fit in at any academic institution. But I went. This lecturer was talking about “blameless shame.” It’s important, he said, to understand this blameless shame. I was at the very back of the auditorium and my light went on.

I remember leaving the university and thinking, “Everything that guy said was about me. I’ve been carrying this shame around and didn’t even realize it was shame.” Blameless shame is when you realize you’ve done nothing wrong; it’s when you realize you were not the pervert who sexually, physically and psychologically abused kids. We were just innocent children who were molested and abused. I had a hard time coming to terms with that part of my life. I was filled with so much hatred.

When I began accepting the concept of blameless shame, I started on my journey of healing. Then I started sharing it with my fellow residential school survivors and other people in our communities who needed to hear it. I’d say to them, “You hear about this thing blameless shame?” I’d explain it to them. Their eyes would go big.

I started getting reacquainted with myself between the age of 35 and 40. It was a slow transition; I was still an addict. I’d go five or six days sober, something would happen, and off the deep end I would go. I never went to rehab. I’d battle it on my own. Even when I was wild in my mid-30s, I could still perform athletically. I was still running track in my 30s; I was still playing soccer. I was 6-foot-3 and 210 pounds. I was sinewy. I think it’s another reason I’m alive today. I played hard in my life in so many negative ways, but I trained hard too. I lifted weights. I was big, strong, fast, agile. By the time I was 40, I was starting to figure out some things.

When I got out of residential school, I had no idea how good an athlete I was. None of us did, even though we would often beat and dominate Settler teams in a lot of school sports. We didn’t know what we didn’t know, eh?

Once I was married, my wife and I went through life surviving as best we could. Thankfully, my wife took care of the family when I was absent; when I was gone for a week at a time, her not knowing if I was alive because I was disappearing from the realities of life.

As out of control as much of my life was, by the age of 23 I was back playing hockey regularly; first in the Commercial League as well as some Indigenous tournaments and events. Between 1975 and 1981, I played for the North Battleford Beaver Blues in the Saskatchewan Intermediate AAA League, high-level senior/semi-pro hockey against teams that were competing to win the Allan Cup (emblematic of national senior amateur hockey champions).

As a hockey player, I can say I was never treated as well as I was by the Blues. I am forever grateful for that. It was the first time in my life, where if you needed skates, you got new skates. If you needed gloves, you got them. You got everything you needed. You would get five dozen sticks to start the season. We even had our names on our sticks. That Blues organization treated me with so much respect. It was the first time in my life that I felt genuinely accepted in Settler society.

I can also say I was treated horribly by opposing players and fans at that time. I was usually the only First Nations player on the team. I was often the only First Nations player in the league. And the rinks I visited, when they folded up the sticks after the game was over, the only one they didn’t fold up was Arcand’s stick. They knew I had to use it to defend myself on my way out of the rink because there were people who wanted to kill the Indian. So, I didn’t only experience it as a child at residential school; I experienced it as an adult athlete. There’s nothing you can think of that wasn’t said or done to me. I’ve experienced it all.

If you’ve seen the movie Indian Horse, everything that happened to the lead character, Saul, happened to me. I was threatened and assaulted – not just on the ice either. I had no desire to club any person over the head; I had no thirst to hurt someone. But if I was threatened and in danger, I was fearless and ruthless. I can’t say I’m proud of those moments, but I will not apologize for any of my actions. The residential school system created a monster.

Eugene Arcand saw a lot of similarities to his own life in the fictional life of Saul, the lead character in the award-winning movie Indian Horse. (Photo Credit: Elevation Pictures)

I was spit on; I had stuff thrown on me. It’s happened to my wife when they found out she was at my game. They would spit in her coffee. When it’s done to me, I can deal with it. But when it’s done to my people, I can’t accept that. And it’s still happening today.

I will go to a AAA midget hockey game in Saskatchewan, and I hear some of the Settler parents, the slurs they are hurling at children they’ve never met in their lives. They’ve never met the First Nations players’ parents. They don’t know if those parents are employed or if they’re trying to be a positive part of society. And (the First Nations players and their parents) are called down like dogs. Spit on. Abused like dogs. And who tries to stop it from happening? No one. If someone does come to enforce it, who do you think will get charged? Who’ll be the one in trouble? Me and my people, that’s who. I say this from experience. I’m not crying on your shoulder. This is real life.

On the other hand, as an adult athlete playing with and against Settlers, other players would come up to me and say, “Where did you learn to play like that?” and “Where did you play junior?” I wouldn’t answer. I would be on a ball field, whacking them out, playing great defence and they would come up to me and say, “Where did you learn to play fastball?” I wouldn’t answer them. I played centre half in soccer; played in the first ever Saskatchewan Summer Games in Moose Jaw in 1972 and people would come up to me and ask, “Where did you learn to play soccer?” I wouldn’t answer them. That’s because I didn’t want to say residential school. I didn’t understand shame, the shame of residential school.

I didn’t learn mental toughness in a way it should ever be learned. I learned mental toughness in residential school. My mental toughness carried me through sports as an adult athlete. And now it carries me through my work when I speak to people about my life for the sake of public education. I prepare the same way; give my all for as long as it takes to get the job done. I go full bore.

I played my sports rough. I never held back. I handled myself okay. If they started getting the best of me in a fight, I would do whatever I needed to in order to survive — pulling hair, scratching, biting, gouging – there isn’t anything I wouldn’t do. Usually when I would see them again, they didn’t want to go anymore. I didn’t win them all, but I made sure they didn’t want to fight again.

I was targeted a lot. I recall on a number of occasions being called on in the first period. I’d tell them, “I don’t want to fight right now, we’ll go later. Let’s play hockey for a while.” They would call me a chicken s–t. That was fine, but I made sure by the time the third period came along, and we had a lead, I’d remind them of the offer. Most times they didn’t want anything to do with me. You have to know how to handle yourself. It was survival skills.

It wasn’t easy. There were times I wanted to quit hockey. I couldn’t handle the racism. Every weekend I’d go to these arenas; it was not a nice experience. The hockey was good. But the behaviour of people in Saskatchewan towards me was what I call normalized horrible.

I would call a friend of mine, my mentor, Ray Ahenakew. Ray was in the generation of Indian hockey players in Saskatchewan who came after Freddy Sasakamoose but before me. Ray played for the Yorkton Terriers and for a lot of senior intermediate leagues. People in our communities still talk about the fight he once had with former NHL/CFL player Gerry James.

Ray knew what I was experiencing. I’d tell him, “I can’t do it anymore. I can’t handle this s–t anymore.” He told me, “You can’t quit, buddy. You’ve made it to this level, and you have to keep going because if you quit, they’re going to pass judgment on the rest of us.” And how true his words became. So, I always tried to stick it out. I faced all my suspensions. I faced all the strategic moves that were designed to slow me down or cool me down. I’ve tried to live by that, as best I could, in the rest of my life, too.

And I’d fight back as best I could, try to stand up for myself and my people.

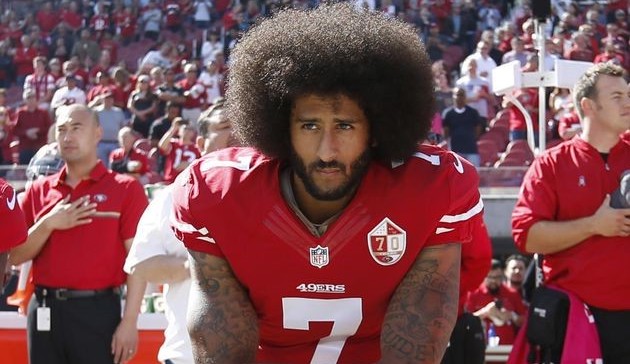

Before games, I wouldn’t stand up for the national anthem. I did it because of the treatment of my people. When NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick first kneeled during the American national anthem to highlight racial injustice in 2016, my friend Richard Mirasty, a very well-respected criminal defence attorney in Alberta, reminded me I was doing it in the 1970s. I remember one time in particular, our coach on the Blues, Merv Borgeson, told me I better stand for the anthem or the referees might give us a penalty. I told him to forget about it, because it wasn’t happening. He kept on me about it and I told him, “If you want me to stand up, I’ll walk out of this rink right now and you’ll never see me again.” He never said another word.

Long before Colin Kaepernick, in 2016, was kneeling to protest racial injustice in the U.S., Eugene Arcand was refusing to stand for the Canadian anthem when he was playing senior hockey in Saskatchewan. (Photo Credit: Mike Morbeck/Wikimedia Commons)

I had some really good coaches with the Blues. Bobby Sheppard, (former NHL forward) Gregg Sheppard’s brother, was one of them. Merv was another. I recall one time when Merv rearranged the lines. He had put me on a line with a couple of players who I viewed as closet rednecks. As we were getting ready to go on the ice, Merv said, “Everyone ready to go?” I told him, “I’m not ready to go. I don’t want to play on that line.” And it was the first line. He said, “Why not, Arcand? What’s the problem?” I told him, “I don’t want to play on a line and have to protect people I don’t trust. I can’t protect people I don’t trust. Put me on another line.”

That really affected the dressing room, but I was not going to put up with that kind of s–t. I was being honest and truthful. Sure, those guys are my teammates, but I also knew some of the things they had said over the course of the years I had played with them. They had to pay their dues back with me before I was going to step up for them. Because when I had to step up for my team and my teammates, I would really step up. I was not a person to start brawls, but if someone was going after my linemates, I’d step up for them.

I liked the line I played on, with two Ukrainian guys, Pat, who went by the nickname Hoyo, and Lionel, who went by Weenie. They were good guys. I liked and respected them. They both could score goals, but they needed someone to go into the corners and do the dirty work. That was my job. I’m feeling for them right now because they’re both Ukrainian. It’s so horrible what’s going on there with Russia.

I made many friends in hockey, both Settlers and Indigenous. I think of my time playing and I think of Gazoo, Dickie, Snazz, Chaboy, Guy, Bruce ‘7’, Greg, Porky, Floppy, Howie, Joey, Eddy, Dale, Tubby, Midge, Albert M, Moe, Filthy, Ron, Louis, Ovide and Abe….so many more.

My last year with the Blues was in 1981; I was getting close to 30 years old. I’d had enough. I still played lower-level hockey on and off until I was 40 but once I started to get my life more in order, between 35 and 40, there were other things for me. My wife and family was one; reconnecting with my culture and getting back what was lost and taken away from me when I went to residential school was another.

NCTR’s spirit name – bezhig miigwan, meaning “one feather”.

Bezhig miigwan calls upon us to see each Survivor coming to the NCTR as a single eagle feather and to show those Survivors the same respect and attention an eagle feather deserves. It also teaches we are all in this together — we are all one, connected, and it is vital to work together to achieve reconciliation.